Introduction

According to the CDC, 60% of U.S. adults live with at least one chronic disease and 40% have two or more (1). Dietary approaches are a cornerstone of managing chronic health conditions. Nutrition plays a key role by influencing inflammation, gut microbiome balance, and overall health (2,3). It is essential for registered dietitian nutritionists (RDN) to understand this dynamic to provide targeted, individualized care.

Understanding the Gut Microbiome

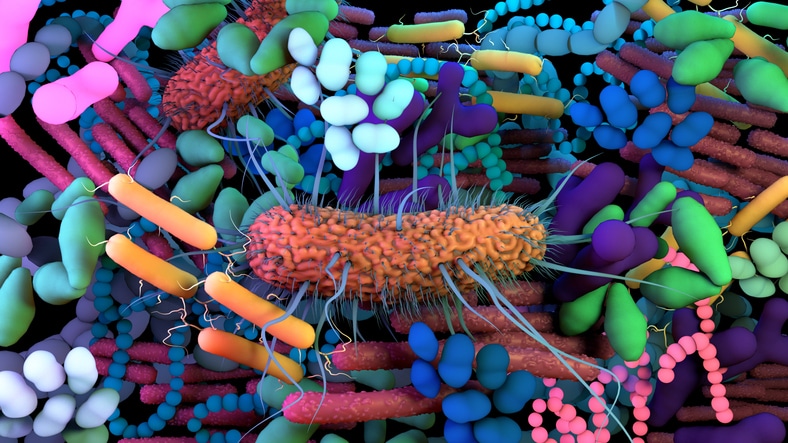

The gut microbiome, found primarily in the large intestine, is made up of trillions of microbiota including bacteria, fungi, protozoa, and viruses. Each plays a role in maintaining microbial balance creating an environment that is either in a state of symbiosis (a close living relationship between organisms from different species, usually with benefits to one or both of the individuals involved) or dysbiosis (an imbalance of microbial species in the body). Diet strongly influences this balance. During digestion, gut bacteria break food down into metabolites that shape microbiome composition and activity.

Common findings seen with symbiosis are increased presence of beneficial short chain fatty acids (SCFAs) and phytochemical metabolites. In contrast, when dysbiosis occurs, a disruption of the bacterial homeostasis results, causing an influx of potentially harmful secondary bile acids, proteolytic metabolites, and trimethylamine-N-oxide products (4).

A variety of factors can impact gut health, especially as we age. Elements such as environment, diet, medication, genetics, and physical activity all play a role in shaping an individual’s microbiome (2,4). Chronic disease can have a detrimental effect on gut health. Dysbiosis contributes to increased inflammation, production of harmful metabolites, increased gut permeability, and lowered immune response. In comparison to a healthy adult, individuals with diabetes, cardiovascular disease, cancer, chronic kidney disease, and/or irritable bowel syndrome tend to have changes to gut microbiota and increased dysbiosis (2,4).

Incorporate Healthy Foods to Improve Gut Balance

Most of the available research on gut health has focused on the impact of different dietary patterns. The typical Western diet is known to be high in fat, sugar, and processed foods. As a result, the diversity of microbiota is lower and the metabolites present support an environment of dysbiosis, increasing the risk for chronic disease.

Dietary patterns emphasizing plant-based foods, such as the Mediterranean or vegetarian diet, can positively affect diversity and richness of the microbiome. These diets increase the production of beneficial SCFAs and phytochemical metabolites, which can help reduce inflammation and improve gut balance. Knowing this, experts recommend incorporating foods that are considered natural sources of prebiotics and probiotics as part of a balanced, healthy diet (3-6).

- Nuts: As a natural prebiotic source, nuts offer the benefits of fiber, polyphenols and unsaturated fatty acids. The type and quantity of nuts consumed can influence gut health, with walnuts and almonds being among the most recommended (3,4).

- Fruits and vegetables: Diets rich in a variety of fruits and vegetables offer prebiotic benefits along with dietary fiber, phytonutrients, vitamins and minerals. Once digested, metabolites from these foods serve as substrates to increase microbiota diversity and richness (4).

- Whole-grains: Whole-grains such as bread, cereal, oats, rice, quinoa and barley offer fiber rich selections which are broken down into beneficial SCFAs. Research suggests that consumption of these foods supports a more diverse gut microbiota and improvement with inflammation, glycemic response, and post-meal fullness (4,5).

- Legumes: Replacing animal-based proteins with legumes provides a plant-based alternative rich in fiber and nutrients. Research on the benefits of legumes on gut health remains ongoing, however, studies have shown an increase in good bacteria and SCFAs following legume consumption (4).

- Dairy: A variety of dairy products including milk, cheese, kefir, and yogurt can positively increase SCFAs and lower presence of trimethylamine-N-oxide products in the gut. Depending on the source, these foods can offer pre- or probiotic benefits (4).

- Fermented foods: Probiotics are naturally present in fermented food selections. Live bacteria cultures promote an increase in healthy bacteria and can be consumed through choices such as kimchi, sauerkraut, kefir, and yogurt (6).

Call to Action

Given the strong connection between gut health, chronic disease, and dietary intake, RDNs can emphasize inclusion of beneficial foods as a priority. The following strategies can support this goal:

- Assess an individual’s eating patterns and encourage a transition from a Western-style diet to a more plant-based diet.

- Focus on variety. Suggest eating different fruits and vegetables to provide key nutrients and offer natural sources of prebiotics and probiotics.

- Encourage patients to cut back on added sugar and non-nutritive sweeteners. Limiting these additions is shown to have a positive influence on gut balance and symbiosis.

- Encourage plant-based alternatives to animal-based protein. This will support a more diverse gut microbiota and increase beneficial bacteria.

- Encourage patients to incorporate fermented foods. While individual tolerance may vary, fermented foods provide a rich source of probiotics to enhance gut health.

References:

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. About Chronic Diseases. CDC website. Updated October 4, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/chronic-disease/about/. Accessed March 31, 2024.

- Mansour S, Moustafa M, Saad B, Hamed R, Moustafa A. Impact of diet on human gut microbiome and disease risk. New Microbes New Infect. 2021;41:100845. doi.org/10.1016/j.nmni.2021.100845

- Anderson-Haynes, S.E. (2021). Harvard Health Publishing. Diet, Disease and the Microbiome. http://www.health.harvard.eduwww.health.harvard.edu/blog/diet-disease-and-the-microbiome-202104212438. Accessed March 31, 2025.

- Hughes R, Holscher H. The Intestinal Microbiome. In: Matarese LE, Mullin GE, Tappenden KA, eds. Health Professional’s Guide to Gastrointestinal Nutrition. Second edition. United States: American of Nutrition and Dietetics; 2023:224-253.

- Tappenden K. Prebiotics. In: Matarese LE, Mullin GE, Tappenden KA, eds. Health Professional’s Guide to Gastrointestinal Nutrition. Second edition. United States: American of Nutrition and Dietetics; 2023:254-264.

- Warren M, Martindale R. Probiotics. In: Matarese LE, Mullin GE, Tappenden KA, eds. Health Professional’s Guide to Gastrointestinal Nutrition. Second edition. United States: American of Nutrition and Dietetics; 2023:265-281.

Want to Learn More?

- Gastrointestinal Nutrition: A Primer for Nutrition Professionals – 25 CPE Course https://www.beckydorner.com/product/gastrointestinal-nutrition-a-primer-for-nutrition-professionals/

- Using Probiotics for Irritable Bowel Syndrome – Short Course

https://www.beckydorner.com/product/using-probiotics-for-irritable-bowel-syndrome-short-course/

Also, search our courses and webinars and manuals for more on this subject.